Theoretical and computational physicist

contact: mgalantephys@gmail.com

Welcome to my personal website!

I am a researcher interested in quantum many-body effects, dynamics and spin transport in condensed matter and molecular systems. You can find more information about myself by clicking on the links below or by scrolling down to check out my main research interests:

Quantum biology

… to be modified!

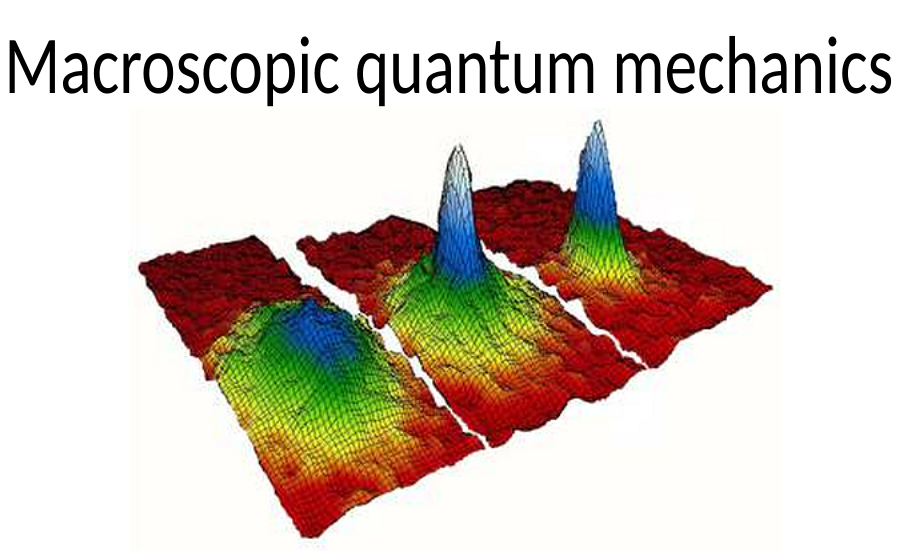

Quantum mechanical phenomena are at the fundations of any macroscopic observable. However, the elevated complexity together with the astronomical number of degrees of freedom involved makes it impractical to directly apply quantum mechanics to mesoscopic systems. Macroscopic quantum mechanics deals with the manifestation of quantum mechanical behavior at larger scales, and is typically enabled by cooperation effects between a large number of particles. My main research interest is identifying crucial factors governing emergent quantum phenomena to then include them in effective and/or coarse-grained models to bridge the quantum world to larger length and time scales.

Entanglement in ultra-cold atoms

Bose-Einstein condensates embody one of the most typical examples of emergent quantum phenomena. They can be realized in systems as simple as ultra-cold atomic gases confined in laser traps, where atoms can move from one potential well to another through quantum tunnelling. The entanglement between the wells then creates quantum states that can be considered as a real-life concretizaation of the Schroedinger-cat experiment.

Further reading: Double well traps

Optical spectra

The inclusion of electron-hole bound states, known as excitons, is essential to correctly estimate the optical response of semiconductors as simple as silicon. This requires the solution of the Bethe-Salpeter equation, which is generally fairly computational expensive to evaluate. I took part to the implementation of a methodology that employs an optimal basis set approach to express excitonic states through a reduced number of degrees of freedom.

Further reading: SIMPLE code

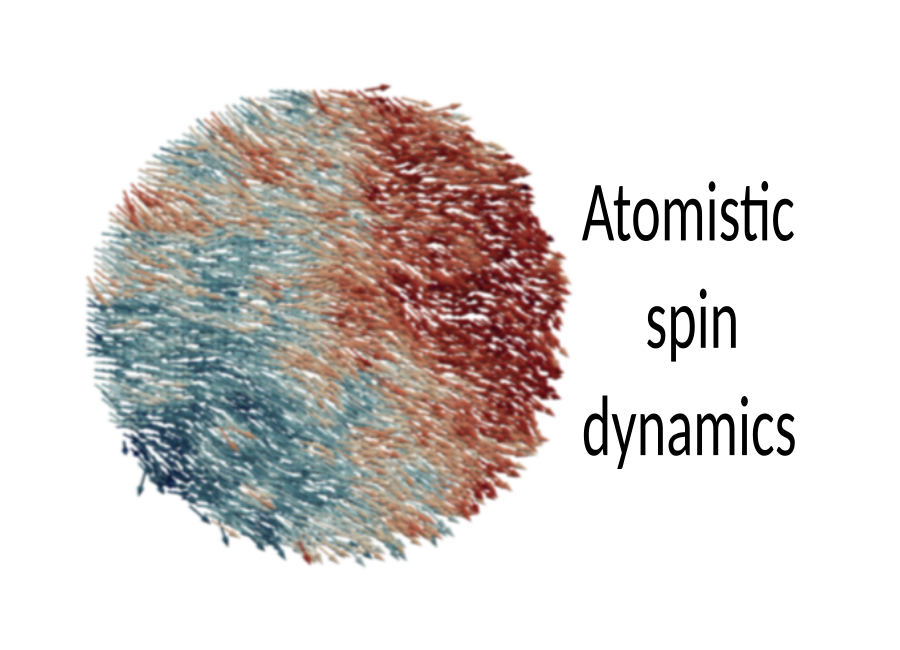

Atomistic spin dynamics

Magnetization dynamics underpins a multitude of modern technologies, ranging from sensing devices to memory storage. The latter can be highly sensitive to the local atomic structure, yet only the behaviour of the global magnetisation matters for most materials relevant of applications. In such cases, the magnetic moments localised at atomic sites can be represented as a classical (Heisenberg-like) spin vectors, and their dynamics can be described through the Landau-Lischfitz-Gilbert equation. I contributed to the formuation of a methodology to use first principles calculations to parameterise atomistic spin models for current-driven spin dynamics in ferromagnetics and anti-ferromagnetics materials.

Further reading: longitudinal spin fluctuations, current-driven spin dynamics

Van der Waals dispersion and dynamical effects

Van der Waals dispersion interactions provide a relatively small energetic contribution, yet can be essential to guide the global dynamics of nanoscale systems. However, such effects become relevant only for systems of 60+ atoms, and their importance for biological systems made of ~10k atoms is of troublesome determination given the high number of degrees of freedom and the consequent high computatioanl cost. I am involved in a project that aims for a continuum description of MBD interactions for polymers, which should be able to shed light on the influence of MBD in polymer melts.

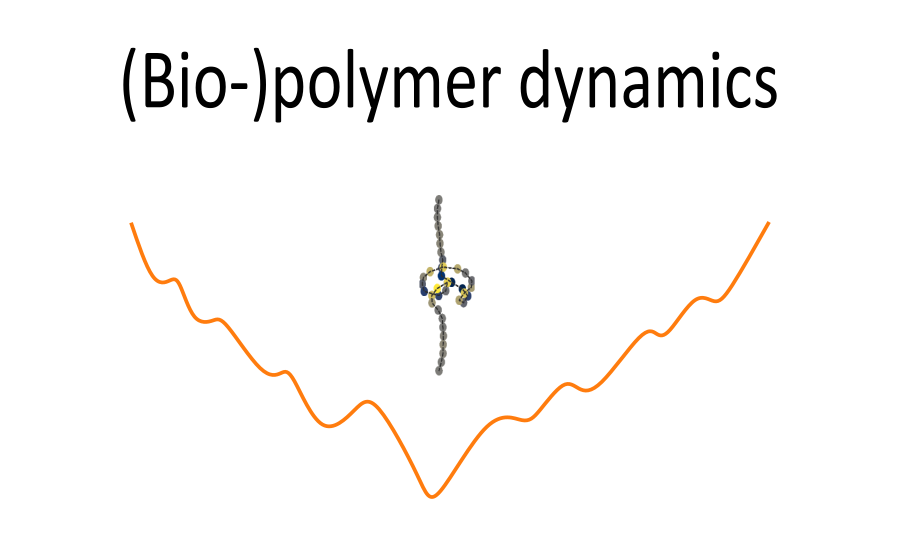

Dynamical effects in (bio)polymers

Polymer dynamics is at the basis of many phenomena of interest from modern science, ranging from biological processes such as protein folding to the systhesis and stabilization of polymer melts for engineering applications. The large length and time scales of such systems, combined with the high level of resolution required, pose a formidable challenge for the molecular modelling community. An additional complication is the presence long range interactions which can be of relatively low magnitude yet essential to control the cooperativity and guide the conformational changes in the system. My focus is in particular on how many-body dispersion interactions can affect the dynamics of large polymeric systems. Early work focused on model polymers, showing that MBD yields an improved conformational search PhysRevResearch.5.L012028. We are also working at analyzing the structural phase transitions from a thermodynamical perspective. More undergoing work is centered on ultra-heavy-weight-polyethelene and on realistic biopolymers.

Main collaborators:

- Prof. Alexandre Tkatchenko, Benedikt Ames, Dr. Matteo Gori, Ian Sosa, Dr. Jakub Leniewicz (University of Luxembourg)

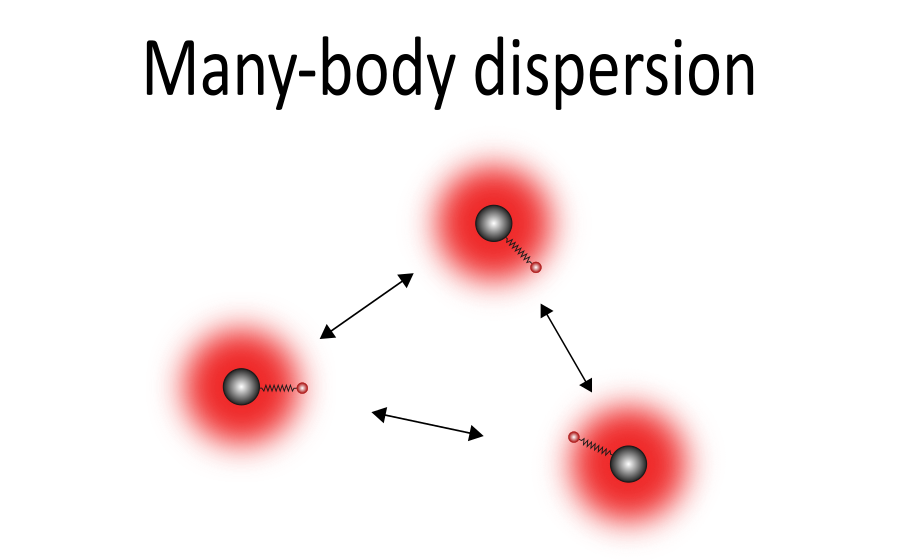

Many-body dispersion interactions

Van der Waals (vdW) dispersion interactions are obiquitous in atomic and molecular structures and arise from the coupling of instantaneous charge density fluctuations. Such density correlations are systematically neglected by density-based approaches (e.g. DFT), thus they have to be added separately. The most common approximation localizes the fluctuations at atomic nuclei, and assumes them to be dipolar and pairwise, obtaining the sttractive part of the Lennard-Jones potential, \begin{equation} E_{PW} = \sum_{i<j} \frac{C_6^{ij}}{R_{ij}^6}\quad\textrm{with}\quad C_6^{ij} = \frac{3}{\pi}\int d\omega \ \alpha^i(\omega)\ \alpha^j(\omega), \end{equation} where the atomic polarizability, \(\alpha^i\), embodies the local atomic environment. The latter can also be used to tailor the frequency, \(\omega_i\), of a quantum harmonic oscillator to effectively reproduce the electron desity response of each atom. It can be shown Ambrosetti2014 that the interaction energy of the atomic oscillators coupled through a dipole-dipole potential accounts nonperturbatively for contributions to the dispersion energy at all many-body contributions at RPA level. The resulting forces are typically longer ranged and become highly sensitive to structural details, as described on another post.

Coarse-graining strategies for MBD

I am currently taking part in the development of coarse-graining strategies to bridge MBD to larger and larger scales. So…stay tuned!

Main collaborators:

- Prof. Alexandre Tkatchenko, Dr. Matteo Gori, Ian Sosa (University of Luxembourg)

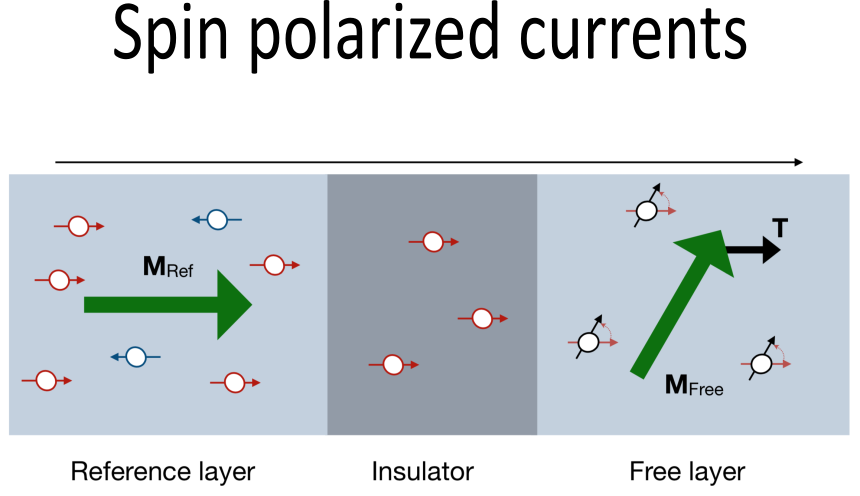

Spin currents

Exploiting the spin polarization of electronic currents plays a pivotal role in the development of miniaturized and energy efficient electronic and magnetic storage devices. For example, giant magnetoresistance (GMR) underpins the working principle of modern read heads of hard disk drives, while effects such as the Spin Hall and the Spin Seebeck Effects are all attractive candidates to generate spin polarization. The main challenges are to maximize the degree of spin polarization and to unveil the interplay between the current flow and the underlying atomic magnetic moments.

Spin selectivity

The use of a material stack or a molecule that filters one spin state is the most spatially efficient way to produce spin polarized currents. Tunnelling barriers are eccellent candidates, although they are effective only for specific material combinations (e.g. Fe/MgO) and require the growth of very clean interfaces. Recently, it was shown that molecular chirality can also be used to filter spin states. The efficient exploitation of chirality induced spin selectivity (CISS) could therefore be the key to the development of efficient molecular electronic devices. Several aspects of such phenomenon are still largely unknown.

Spin transfer torques

The flow of an electric current with spin polarization misaligned with the orientation of the local magnetic moments results in the progressive transfer of angular momentum between current and magnetic layer. In other terms, the spin of conduction electrons rotates while traversing the magnetic slab, therefore exhorting an effective torque on the local magnetic moments. The latter is known as spin transfer torque (STT) COMPLETE

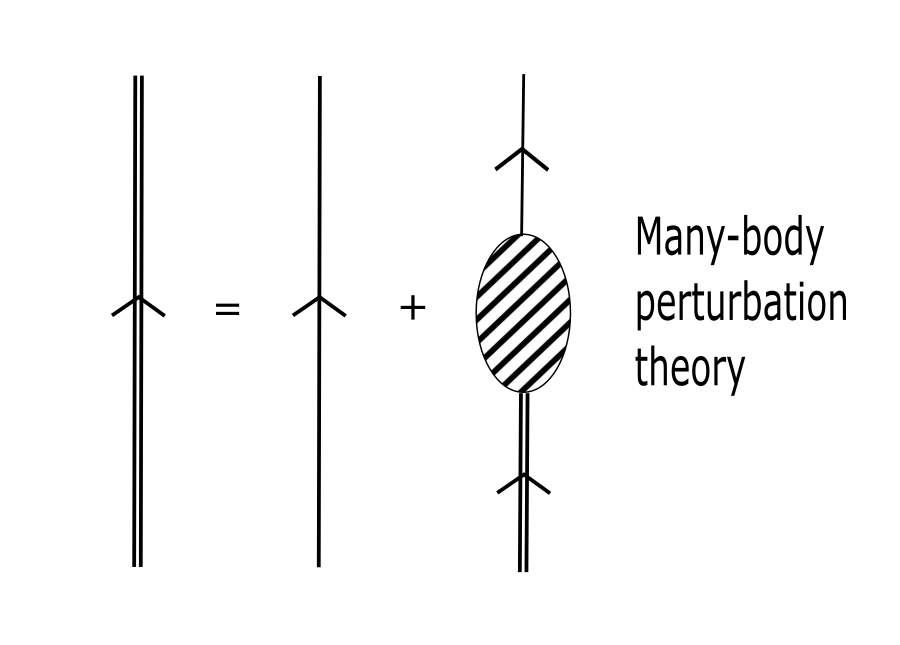

Many-body Green's functions

A major portion of the electronic structure calculations performed today rely on the solution of the Schroedinger equation in the independent particle picture (e.g. KS-DFT). Nevertheless, several phenomena critically depend on either higher levels of correlation or on thermodynamical conditions that elude the capabilities of DFT approaches. Green’s functions (GFs) are the ideal mathematical tool to extend DFT because:

- given the GF of an electronic system any related property can be calculated;

- a perturbation theory can be naturally defined, and the influence of additional factors (e.g. phonons, higher order correlations, ...) can be readily included given the relevant self-energy;

- they can be tailored to include couplings to reservoirs and non-adiabatic interactions with the environment.

Excitons and optical properties

Considering electron-hole pairs is essential to correctly predict the optical response of materials as simple as bulk Si. This can be done by solving the stationary equation of motion for the 2-particle (4-body) GF, known as the Bether-Salpeter equation (BSE). I contributed to the implementation of such methodology in the SIMPLE code, now part of the Quantum Espresso suite of DFT codes.

Quantum transport

The study of how electric currents propagate across nanoscale structures is instrumental for the development of novel electronic components. Quantum transport calulations require the system of interest, also called extended molecule (EM) to be contacted to two (or more) electrodes that serve as particle reservoirs. This makes the overall system infinite, and therefore described through an infinite dimensional Hamiltonian. Green’s functions, however, allow to write the interaction between each contact and the extended molecule through an effective self-energy that only depends on the degrees of freedom of the EM {REF}. The Green’s function for the EM then becomes finite, therefore treatable. COMPLETE

Atomistic spin dynamics

Magnetic properties serve as the foundation for various cutting-edge technologies, encompassing a wide range from sensors to memory storage devices. At the nanoscale, the arrangement and characteristics of atomic species have a profound impact on the overall dynamics of magnetization. Atomistic spin dynamics (ASD) employs Heisenberg-like Hamiltonians defined upon parameters tailored to reproduce the magnetic properties of a given material. The latter can be estimated with first principles methods such as DFT, effectively enabling to bridge quantum mechanical information to lengths up to tens of nanometers.

Current-driven spin dynamics

The ASD Hamiltonian can be extended to include the interaction between spins and external drivings, such as spin-polarized currents. Quantum transport calculations can then be used to estimate effective torques acting on atomic spins, therefore completing a multi-scale picture of current-driven spin dynamics.

Further reading: multiscale simulations of current-driven spin dynamics

Longitudinal spin fluctuations

Although most materials can be represented through an Heisenberg Hamiltonian, in many cases the need of many parameters can be a strong deterrent. For example, magnetic moments at Pt sites in L10FePt is heavily dependent on the orientation of moments at Fe sites. This can be solved rigorously by introducing higher order in the magnetic anisotropy parameter, which can be computationally expensive. To overcome this complication we extended the ASD model to accomodate for dynamical spin length variations. HOW IT WORKS

Further reading: paper

Main collaborators:

- Dr. Matthew Ellis (University of Sheffield)